WORK

After years of collaboration with Jason, he would for the first time “introduce” to his public, who know him through his artwork, his second skill as a therapist. When I visited his workshop (separated by a wall from his therapy office), in order to see his new work and talk about his upcoming fourth solo exhibition, I was introduced to an almost complete at that time, new series of paintings. Even though one could recognize the artist’s style, was nevertheless amazed by the manner in which he managed to develop his painting essence by combining his own various visual idioms. While in a second series of works, all of Jason’s familiar, multi-colored figures seemed to have jumped from the canvas on tiny flat sculptures in an attempt to become visible from more than one side. As in its entirety the work presents an intense diversity (in terms of style and theme) it was difficult to decide on the central idea of the exhibition. Still, the answer was right before our eyes: this group of paintings and sculptures signifies for the artist a new era both as to his artistic and personal development, while still being deeply connected to all that came before. In other words, it is a work that walks the line between the precedent and the new and reveals a level of experimentation, pursuit and vacillations. A work that in spatiotemporal terms could be found in an in-between (stage). The in-between, which has been extensively analyzed in the poetic (Mallarmé) and overall culture discourse, suggests a limbic space devoid of exact location. Thus, every certainty is placed under negotiation and nothing is considered given or fixed. Under these conditions, everything complements another, transforms and is not yet fixed to a certain condition, which would mean an end, a death. Life itself occupies the space between conception and death (N. Wilson, 2019, p.1). According to Derrida the in between is linked to the notions of the interstice, spacing (espacement), différance and is therefore a productive medium that allows intensities, contradictions and diversities to be revealed as such. If this could be transformed into an architectural element, it would be none other than a threshold, a passage and peristyle, a portico and a gate, a door and antechamber an arch of triumph.... that which is found in between, a space between things. (G. Teyssot, 2013, p. 87). For T. S. Eliot the meaning of a poem is somewhere between the poem and the reader. Because the work of art is that which opens the space between the world and the people who perceive it. The works of the exhibition come exactly from that in-between space which in this case could be “translated” in various ways. As to the style adopted by Jason: Between schematisation and a more realistic visual language, between abstraction and representation, between drawing and color, void and filled, gouache and ink. Between words, shapes and forms. Let us take the painting “Always there” for example. The artist continues working on the black background that was prevalent in his previous solo exhibition. This time, that background reminds us more of a school blackboard. And again, in the backdrop and to the right we come across his schematic mythical figures. Yet, in the forefront we find three shapes coming from a completely different vocabulary, which are not invented by the artist but refer to images he himself has seen and which at the same time are associated with childhood experiences. On the other hand, looking at the paintings "Something dead/something alive” and “In-between” we recognize common patterns, such as completely abstract animal forms (from the series with the uncanny creatures), which seem to have invaded into an almost realistic portrait of the artist at a young age. Hand-made paper in one case, canvas in the other. Bold outlines (Something dead/something alive), drawing that seems to dissolve in color (In-between). However, also as regards his 3-dimensional work, Venetsanopoulos seems to hover between painting and sculpture, surface and pedestal. And thus, he invents an intermediate solution. He maintains intact the black surface (metal instead of canvas) with linear “extraterrestrial” figures traversing it, but he is not limited to just a single side of the work being visible. Using tiny, marble bases as supports for this series of works, he makes each surface visible from both sides, equally filling them with drawings. Venetsanopoulos’ new work transfigures an internal bridging process between his two capacities (artist - therapist) and also events that left a deep trace in his memory and even various influences from readings, trips, images, sounds. In therapy (in this case Gestalt therapy), language is the therapist’s main tool in approaching and understanding the relation of a client’s inner self with the outer environment. In the artist’s words: “It seems that the therapeutic characteristic of therapy lies in the process itself. On what happens while we talk”. Painting on the other hand is based on observation and decoding of things, and in this case, color is the tool. In other words, a medium beyond language: Painting is defined as the attempt to render visible forces that are not themselves visible (G. Deleuze, 1981, p.56) with the use of color, which is located at the limits of language pulled from the unconscious into the symbolic order (J. Kristeva, 1982, p. 216). Each work is composed as a palimpsest, made of different elements stemming either from the artist's memory or imagination, or from myths and stories he has heard. And it is the vehicle through which he is called to communicate using the space between the artwork and the observer, the self and the other. Matina Charalambi Art Historian - Curator

IN BETWEEN

CUTTING EDGE

CUTTING EDGE

a project for DESFA

2020

Jason Venetsanopoulos – Project δesfa

Jason Venetsanopoulos creates a unique work of art for δesfa, attempting to use a symbolic visual language to creatively reflect the company’s vision and goals.

The artist creates a complex artwork, arising from the pairing of painting and sculpture. In essence, he “deconstructs”, one could say, the painting space and condenses it in a geometrical structural form, which is the main key in approaching the issue of movement. The artwork transforms into a space-time unit, mentally expanding space to all possible directions (the role of the quadrangle), while revealing at the same time the symbolic function of the sculpture, as a benchmark that indicates the landmark to which it is bound.

Interest revolves around two basic parameters. That of structure, with influences from the constructivist movement of Modernism and that of the corporeality of the work, meaning the volume and tangibility of the raw material. However, the key characteristic that seeps through the core of the piece, both literally and metaphorically, is the conversation between the natural element with the artificial one.

According to constructivist precepts, the lead is given to the construction dimension of an artistic creation, which is incorporated into the framework of industrial technology. Venetsanopoulos attempts his own approach: into the circular metal structure he incorporates a marble surface, on which he has painted, in juxtaposition between the industrial and the hand made. Marble, a carrier of historical memories, refers to the ancient Greek past, while at the same time it is a natural, crystallized rock that encompasses the passage of time in the form of concentrated plications. The trapezoid shape selected by the artist is in contrast to the uniformity of the metal ring that surrounds it, which is linked to the concept of recycling and the circular economy, not only symbolically, but also literally, as it constitutes a part of a cylindrical natural gas pipeline that is reused and repurposed.

Thus, we see that the artwork is ruled by a series of symbolic sequences in an ongoing discourse. Apart from the metal frame, the circle is repeated in the movement of the painted forms on the one side of the marble plaque. A symbol of the Nietzschean “eternal return”, perpetual recurrence of itself in the infinite universe, and with references to Wassily Kandinsky’s “Circles in a Circle” (1923), a study of the circular shape with all intellectual and conceptual implications.

The presence of figures is not missing from this piece, always in sync with Venetsanopoulos’ visual vocabulary. His typical hybrid forms, something between eerie heroes and uncanny imaginary beings, they seem to also carve a circular course on the white marble background, leaving traces of blue and green hues, same as those in the δesfa logo. At the same time, they refer to the hieroglyphic language, as well as to their modern Greek interpretation by Yiannis Moralis. In endless movement they move together in an irregular swirling, which brings to mind Matisse’s “La Danse” (1910), stressing the necessity of maintaining contact with and giving to human beings.

Matina Charalambi

Art Historian

NEOMYTHICAL

NEOMYTHICAL 2020

What would an illustrated pop mythology look like today? A post-modern tale inhabited by all those capricious ghosts, eccentric spirits and benevolent monsters whose purpose would be to offer a symbolic antidote to our frantic but nonetheless boring current reality?

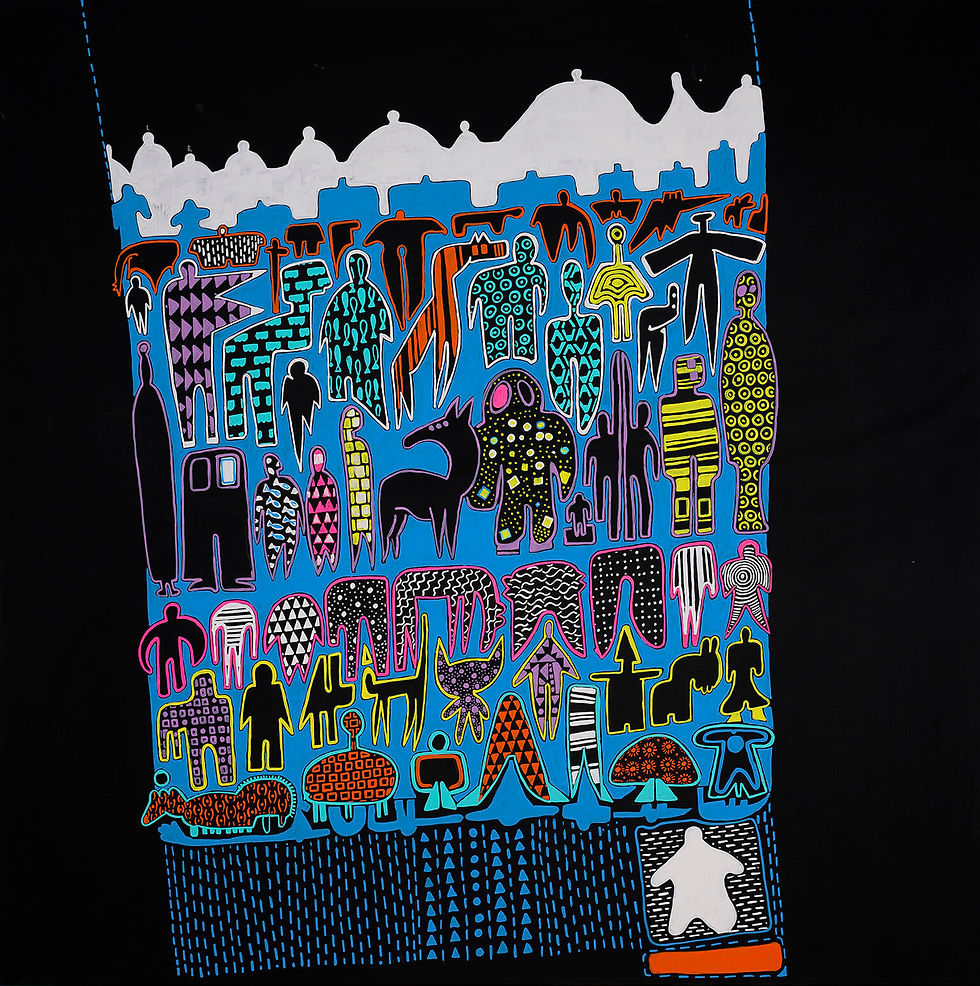

In his third solo exhibition Jason Venetsanopoulos wrangles a possible answer... Developing an automatic illustrative script - spontaneous and almost mechanical - he weaves the thread of a paradoxical, fragmented narration from which fluorescent sprites and erratic hybrid beings pop up to compose an extravaganza of the absurd to the tunes of Brian Eno and Peter Gabriel. Driven by an urgent desire to return to a lost Paradise of youth, the artist creates a series of paintings on canvas with a sternly restricted gamut of six clean colors, which act as images/fragments of a mythological narrative.

An extravagant giant with a helmet adorned with a fish as a crest, a quirky machine with legs operated by a robot wrapped in an azure halo, zoomorphic monsters in flamboyant fluorescent costumes, an orange man/fish are just some of the two-dimensional forms parading before us, distinctive figures... in that border line area where the mind wavers and fantasy blooms. In improvising these composite beings, Venetsanopoulos attempts to re-enchant the modern world seeking the beginning of art in the primary stage of artistic creation, when images had a supernatural, protective power.

In his latest work, which maintains a clear relation to his previous work, while at the same time it constitutes an imaginative evolution, one could identify a primitive element, filtered through an adolescent desire covered by a neon mist. This element can be seen both in its almost schematic figures with the bold outlines and in what these stand for.

If we look back to the first artistic expressions, mythograms, to quote Leroi Gouhran, was initially composed of abstract, symbolic, expressive points which later evolved into the fundamental realistic representations of paleolithic painting, we notice one obvious requisite: a myth's the visual representation. The same applies to aboriginal art, from which the modern skeptics of the new order of the time borrowed their “ammunition” (e.g. Gauguin, Κlee, Picasso, Mirο, etc.).

Myths have been subject to various approaches and interpretations. Among the most significant are those of Levi-Strauss as a means of human communication or of semiologist Roland Barthes, who sees myths as a language per se. However, basically myths are nothing more than a narrative and this narrative is of a creative nature and roots in animism: Primordial people establish a host of spiritual beings in the world, considered to have good or bad intentions, according to Freud in Totem and Taboo. All these inconceivable daemons and capricious gods are in essence a reflection of the internal world in the external reality.

Through the images he presents to us, Venetsanopoulos seems to aim towards the formulation of a personal, innermost myth. A myth revealed piecemeal through a peculiar visual code where Egyptian pictograms meet the symbolic vocabulary of Keith Haring, Cycladic idols are dressed with the playful, geometrical motifs of the Memphis Group and the cave paintings of Lascaux are transformed into miniature billboards of the 80’s. His goal? A flashback to a state long forgotten, when interpretation of the incomprehensible could be achieved through the construction of a parallel, metaphysical universe, where all possible explanations could coexist.

Matina Charalambi

Art Historian

THERE IS AN OTHER WORLD BUT IT IS INSIDE THIS ONE

THERE IS AN OTHER WORLD BUT IT IS INSIDE THIS ONE

2017

In his second solo exhibition “There is another world, but it is inside this one”, Jason Venetsanopoulos presents a series of whimsical miniature ink-on-paper drawings. It is a bizarre parallel universe of personal symbols and forms, with humor being the central element.

These works could also be characterized as “two-dimensional miniatures”. They are distinctive due to their particularly small size that renders them almost indiscernible and their notably plain lines that, instead of avoiding the whiteness of the empty page, they decidedly don’t resist any tendency for visual verbosity.

Venetsanopoulos disrupts the rules of perception In a playful manner, engaging the viewers in a process of adventurous discovery. He invites them to develop an intimate relationship with the works, since they need to literally and metaphorically come closer to see them. Thus, the viewers can get involved in the process of viewing itself.

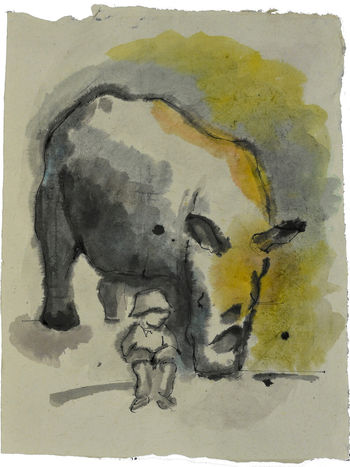

The microcosm that Venetsanopoulos sets up is inhabited by imaginary, lilliputian characters creating a feeling of tender intimacy as if arising from a child’s dream: brindled roosters wondering about their existence, travelling elephants carrying their luggage under the auspices of anthropomorphous spirits, flabby creatures calling Spring with their discordant song… All these figures are nothing but self-reflections that acquire mythological dimensions in Venetsanopoulos’ visual idiom. They constitute the depiction of fears, urges and desires that in myths were usually represented as monsters, spirits and elves. Such imageries, after being rationalized and exorcised within modern world, were finally forced to return to their place of origin, the unconscious.

Venetsanopoulos’ bizarre creatures have a strange way of interacting with each other, always hiding a melancholic solitude behind their comical facade. Either appearing in groups or spurting out of the paper by themselves, they all carry a distinct narrative, a story that the artist intentionally leaves open for the viewer to complete. This is the reason why the illustrative elements of the drawings are frugal. They are only limited to those details necessary to generate imaginary scenarios like the haiku rhymes, the brevity of which leaves them open to interpretation. Hence, each drawing is a fragment, like pages of a storybook scattered randomly arround the space.

Matina Charalambi

KOAN & OTHER ANALOGIES

KOAN & OTHER ANALOGIES

2015

Koan

In the Zen tradition, a story or question by the master, which raises great doubt in the student and awakens their insightfulness.The short paradoxical narratives of Koan, jolt our everyday logic and provokes personal engagement by illuminating the noble or trivial, the timeless and transient, challenging our commonality of sharing.

Other Analogies

Through fragmented images marked with ink, gouache, pen and oil pastels on handmade paper from India; Ideas, fears, loves, obsessions, drives and lust are all translated into matter, transformed into a blot of ink on paper fibers. Crippled figures semi-transfigured as mythical gods, and animal-like creatures, narrate uncompleted myths and rough ideas. A harmonically dissonant balance of noble disorder, Koan and Other Analogies moves you silently toward fulfilment, without asking you to reason why.

DRAWING

01

COMMISSIONS